Written for Northfield Mount Hermon Alumni Magazine, July 2002:

Led Balloon Jug Band Rises Again

By Max Millard

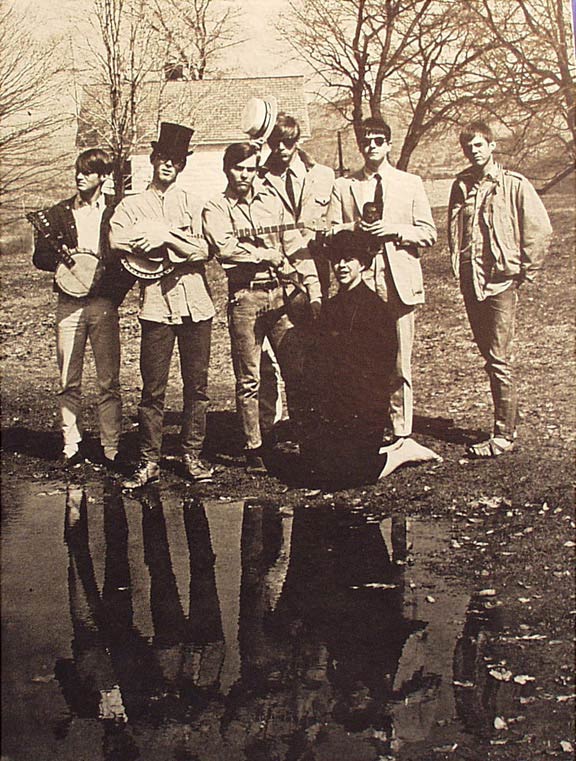

In the fall of 1966, seven Mount Hermon seniors under the leadership of Bruce Burnside formed a group called the Led Balloon Jug Band and began to hold regular practices at Camp Hall. Burnside, president of the school's folk music society, conceived both the name and the repertoire, drawing mainly from the recordings of the Jim Kweskin Jug Band, a popular act on the folk music circuit.

|

| Led Balloon Jug Band, 1967 |

Jug bands have been traced back as far as 1900, and reached their first peak of success during the 1920s. Originated by black musicians in the American South, they featured not only standard country instruments such as guitar, mandolin and harmonica, but also a variety of homemade instruments made from everyday household items. These include the kazoo, the washboard, the washtub bass, above all, the empty whisky jug, which produces a deep, resonant sound when held up to the lips and blown sharply.

The Great Depression of the 1930s brought an end to the early jug bands, but the musical form made a comeback during the folk music revival of the 1960s. Burnside, a jack-of-all-instruments and music collector, heard the new generation of bands, and during junior year he began recruiting students to join his own group, seeking those who already showed some skill on a folk instrument. He lent out his albums over the summer so that prospective members could learn their parts.

When competently performed, jug band music hits the listener's ear like a bat striking a ball. Raucous, rhythmical and bluesy, with each instrument standing out distinctly, it shouts with the joy of life. The lyrics are rooted in 1920s culture -- humorous, sentimental, mildly racy, yet always respectful of women.

The lineup of the Led Balloon consisted of Burnside on guitar, Dick Upson on jug, Will Melton on mandolin, Craig Roche on washtub bass and guitar, Chris Crosby on banjo -- who all doubled as singers and kazoo players -- plus two harmonica players of very different styles, Jim McBean and myself. While I concentrated on the leads, McBean played a lower-pitched rhythm section of his own invention, giving the music an unusual depth and fullness.

The Led Balloon performed numerous concerts at Mount Hermon, Northfield and other prep schools, but the band's proudest moment came on Saturday, April 9, 1967, when we entered Ace Recording Studios in Boston and spent most of the day cutting 13 songs for our first and only album.

|

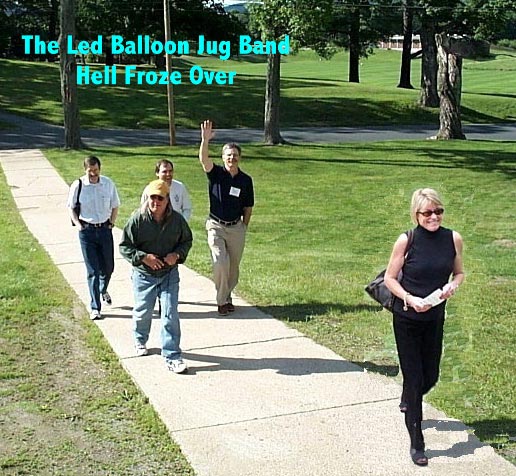

| Led Balloon Jug Band, 2002 |

Burnside independently signed a contract with the studio to pay $800 for the production of 500 albums, then collected enough money in advance from curious students to cover the down payment. This was because school authorities didn't support the Led Balloon as they did the official rock group, the Hermon Knights.

Recalled Burnside: "I never gave the school the school the power to veto the album project and they never took enough interest in us to learn about our plans. I tried to have the album stand as a musical testimony to the band members rather than as Mount Hermon students."

Five members of the band had an open weekend, so we left Mount Hermon on Friday afternoon and arrived in Boston in time to get a good night's sleep at a hotel. But Burnside and Roche had used up their weekends, and had only an overnight on the books. On Friday night at 10:30, they slipped out of the dorm, met the son of a faculty member whose Volkswagen bug was hidden in the woods on campus, and got a ride to the Greenfield bus station, dragging along two guitars and a washtub bass. They clattered into the Boston hotel at 5:30 in the morning, only to find that the Led Balloon had been forced to find alternate lodgings, destination unknown.

With virtually no sleep, Burnside and Roche stumbled to the studio, located in an alley off Tremont Street, and waited for the doors to open. The recording engineer, a jaded old-timer, set us up behind microphones, took a seat behind the soundproof glass partition and signalled us to start. McBean developed a nosebleed that wouldn't stop, and had to be propped upside down with the microphone on the floor so the blood wouldn't drip into his harmonicas.

We had a guest vocalist that day, Norma "Sam" Schreiber, a senior at Northfield with a devastating contralto voice who had rehearsed with Burnside for the occasion. Accompanied only by guitar, she laid down the track "Richland Woman," a suggestive song about a restless housewife whose husband is out of town.

We did most of the songs in one take. When Bruce requested a retake, the engineer would sometimes shake his head benignly and say, "No, that was fine."

Peter Henwood, a Mount Hermon senior from England who had a pilot's license, promised to give our album a spectacular send-off by delivering the newly-pressed copies to the campus by airplane. Discovering that they were too heavy, he instead buzzed over the campus holding a single copy out the window and waving it to the students below. The faculty, unaware of what was happening, alerted the FAA about the strange sight.

The album sold for $5. We made enough money to cover all our expenses, and were left with 15 copies each to dispose of as we chose. In the years after graduation they were gradually dispersed to the world, until most band members no longer had a playable copy.

Burnside was the only member who became a professional musician, developing into a songwriter, multi-instrumentalist, producer, music historian, and leader of a string band, who kept a busy year-round schedule of performing and recording. Two others had careers in the entertainment field: Upson spent 15 years in radio broadcasting, and Roche became owner of a restaurant/nightclub in Oklahoma City. The rest of us continued to fool around with music, but never again reached the heights we had achieved as Led Ballooners.

Somehow, all seven band members plus Sam Schreiber stayed in touch with the school, at least to the extent of having our addresses and phone numbers on file. In February 2002, with the 35th reunion looming, we all received a surprise call from Will Melton, the Mount Hermon class secretary and the incoming president of the NMH Alumni Association.

Most of us probably remembered him as the skinny kid from Virginia with the dripping Southern accent and the high, sweet singing voice who could barely play the mandolin. But in the intervening years he had matured into a formidable can-do person, an education professional with a permanent link to NMH dating back to his five years working for the alumni office in the 1980s.

After some initial chitchat, he got to the point: he wanted to get the band back together to perform for reunion. Could we come?

We were spread all over the country: Massachusetts, Vermont, Rhode Island, Minnesota, Wisconsin, Oklahoma and California. Most of us had not been back to the school for decades, and had no plans to return this time.

Melton pressed ahead, writing to us: "Because the world of recorded jug band albums is so minuscule, we probably rank among the top ten best ever. What else have we done in our lives that falls into that category?"

One by one, realizing the once-more-in-a-lifetime opportunity -- and possibly hoping to cut a live album -- we fell into line. By early March, all eight of us were committed to make the trip.

Fortunately, Melton had preserved a mint copy of our vinyl album. He copied the soundtrack into his home computer, scanned the original artwork, and created a CD for everyone in the group. Burnside wrote out the chord charts for all the songs in the appropriate keys and sent them along. We had to do the bulk of our practicing alone, because there would be time for just two full practices together before taking the stage.

Most of had been away from music for so long that we didn't even own an instrument to play. Crosby purchased a banjo and Melton a mandolin for the occasion. McBean and I stocked up on Marine Band harmonicas for the five keys we would need, and began to reacquaint our lips with the right holes. Upson tested the various jugs currently available and settled on a plastic orange juice container. After hearing the CD, he sent these words of encouragement to his ex-bandmates: "Even though the record sounds better than I remembered, it's probably just as well most of us didn't pursue a musical career."

On Thursday, June 6, three band members arrived at Northfield's Hillside House, our class headquarters, and held our first practice. All others except Upson rolled in on Friday. Although some of us had met at previous reunions, in most cases we hadn't set eyes on each other for 35 years. As each newcomer stepped into the room, hugs, rude greetings and quick rejoinders were exchanged all around, while carefully avoiding references to gray hair and protruding waistlines.

We were scheduled to play two concerts on Saturday night -- an "unplugged" one in Hillside's downstairs lounge, followed by an amplified one at Mount Hermon's Music Hall.

Melton was a better mandolin player than ever, although he no longer had the vocal range of early youth. Burnside frowned every time he picked up the $300 instrument, noting that you really couldn't buy a half-decent one for under $5000. When Crosby boasted that he had been practicing for three weeks, Burnside shot back: "Let me see your calluses."

Roche appeared with a washtub bass that was still in pieces -- a large square aluminum tub, a broomstick for the neck, a nylon parachute cord for the string, and various screws, bolts and braces to hold it all together. When he donned his thick leather gloves and began strumming, the band suddenly had its heartbeat back.

Next he pulled out a washboard, which immediately brought requests for him to do their laundry that night. Brushing off the insult with his familiar throaty chuckle, he placed a thimble onto each finger, squeezed the instrument between his knees and launched into the clackety sound of a train starting up -- the opening for "Mobile Line."

Burnside hadn't brought his own guitar, and the only substitute at hand was a learner's model with a warped neck that kept wandering out of tune. Melton made inquiries around campus, and finally secured a 12-string guitar with six strings. It stayed in tune well enough, but the strings were spaced so far apart that Burnside had trouble finding the notes. McBean saved the day by driving back to Vermont and borrowing his wife's guitar, which was both tunable and playable.

It didn't take us long to sound like a band again. When the six of us were immersed in the music, our mistakes were smothered by the sheer weight of the sound. Schreiber took her turn, singing to the delicate finger-picking of Burnside and bass playing of Roche. She had evolved into an authentic torch singer, with a voice slightly deeper but more expressive than before.

We ran through all the songs at least once that day, doing some of them two or three times, and often adding verses or changing the arrangement. Burnside, our musical director by default, tried to extract the best possible performance he could from us. He scribbled feverishly on the chord charts, and spent much of the next 24 hours copying the changes for others, muttering all the while.

Our final rehearsal was in Stone Hall on Saturday morning. Waiting outside the building was a tall, wiry man holding a gallon jug, whom I recognized (by the jug) to be our missing band member, Dick Upson. He had been practicing the songs in his garage several times a day for the past week, and he was ready. Melton said: "Yes, ready to puke from hyperventilating."

Upson brought a boxful of special edition T-shirts imprinted with our 1967 group photo and the name he had invented for our revival, the "Hell Froze Over Tour."

|

| cover of band's 2002 CD |

|

| Sam Schreiber performs with the band, June 2002 |

"Don't let the groupies rush the stage," he warned. "Our pacemakers might short-circuit. They might not let us back in the nursing home."

When Roche made his late entrance to the practice session, the entire band was together in one place for the first time in 12,780 days. Upson observed with uncharacteristic solemnity: "The musical circle has been completed."

There was one more important piece of business that day -- our class's softball game. In the previous reunion we had humiliated the class of 1972, and they refused to play us again. So we agreed to take on the class of '77. Besides having a 10-year physical advantage, they had a much larger turnout of alumni to choose from. To show their seriousness, they even brought a large collection of baseball gloves. Our class had practically none, and had to borrow our opponents' each time we took the field.

The class of '77 jumped to a 2-0 lead on a pair of fielding errors, and grew so confident of victory that they broke out the beer for an early celebration. The class of '67 dug in, shook off the jitters and started to score runs.

Most of the jug band members played. Melton, jumping high to catch a fly ball, landed one-footed on second base and heard a crunch. He limped off the field, and later learned that he had broken three small bones. Burnside, sliding into home plate on both hands, jammed his right thumb so badly that he had to cancel the recording time he had reserved in a studio for the following week.

The final score was 20-8, class of '67. But it came at a price: Melton could barely walk, even with a cane, and would need to perform that night on a stool. Burnside, like the trouper he was, agreed to play through the pain.

That evening there was a cookout in front of Hillside, a prelude to the opening concert of the First Grand Revival of LBJB. Upson couldn't eat, and asked the chef to set his reunion dinner aside for later. It wasn't from nervousness: blowing a jug resembles the gag reflex, and anyone who's not careful can wind up with more than just saliva in the bottle.

By the time we took our places at the front of the room, it was filled with 50 curious onlookers sitting in respectful silence. After some irreverent remarks, we kicked off with an instrumental, "Jug Band Waltz," which ended in a wave of laughter and applause.

Melton took the spotlight next, singing lead in the melancholic "Overseas Stomp," with its references to World War I and Charles Lindbergh:

Oh mama how can it be You went way across the sea Just to keep from doing that Lindy Bird with me.

All singers and instruments had their moment to shine, from the kazoo chorus of "I'm Satisfied With My Gal" to Schreiber's show-stopping version of "Richland Woman." She turned it into a dramatic stage piece, sashaying around the room in her clinging dress, mussing men's hair between verses, and gesturing to her grinning husband in mock disdain. When she finished, the whole room rose to its feet in appreciation -- except Melton, of course.

At Mount Hermon, we entertained a crowd that was twice as large, made up of four generations of alumni, some of whom had probably danced the Lindy Hop themselves. Our electrified sound filled every crevice of the hall. Burnside had cautioned us to ignore the sound from the loudspeakers, or we might get behind the beat. In the third song we suddenly lost it, plunging ahead like a wagon sliding down a hill sideways. After that we recovered and gave what seemed like the performance of our lives. A cacophonous final standing ovation -- led by our own class members in the rear -- and the revival was over.

The next morning, as we headed back to our separate lives, we heard many words of praise, but our classmate Jim Johnson perhaps put it best when he said simply: "They pulled it off."

Upson, the first to leave, commented: "I'm just glad it's over. I'm tired of being pursued by Will and terrorized by Bruce."

In the days that followed, Will sent an e-mail thanking the band members for making it back. He gave the biggest credit to "our fearless leader Bruce to whose inspiration we owe everything." Using his best anatomical metaphors, Melton wrote: "He laid out the music to make the rest of us toe the line and played his heart out as his thumb ached."

His e-mail contained a warning: "To think that we came together after all those years and entranced two distinct audiences is truly remarkable. This may not be the last revival of LBJB."

The Hillside concert, with its flubs, flashes of brilliance, and ecstatic crowd response, was recorded for posterity. Both it and the band's first album are available as CDs; all proceeds will benefit the NMH Scholarship. To order, please send $12 per CD and specify "Led Balloon Jug Band" (1967) or "Hell Froze Over Tour" (2002). Checks should be made out to NMH and mailed to Will Melton, 1 Lamson Road, Barrington RI 02806, email wmelton@risd.edu. He will fill the order and forward the check to NMH. Please enclose three $1 bills to cover the costs of a padded envelope and postage.

| [Top] |

Written for Northfield Mount Hermon Alumni Magazine, October 1993:

Lee de Forest, Class of 1893:

Father of the Electronics Age

By Max Millard

|

If the name Lee de Forest sounds unfamiliar, you can always look it up in the Encyclopedia Britannica. The current edition gives him two-thirds of a page, beginning with these words:

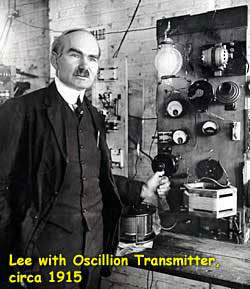

"Inventor of the audion vacuum tube, which made possible live radio broadcasting and became the key component of all radio, telephone, radar, television, and computer systems before the invention of the transistor in 1947."

A Mount Hermon student for two years, and a graduate of the class of 1893, de Forest was Guglielmo Marconi's chief rival for king of the airwaves at the dawn of the 20th century. When Marconi transmitted the letter S across the Atlantic by Morse code, de Forest was next to duplicate the feat, sending 572 words. In 1915, when AT&T introduced transcontinental telephone calling, it was de Forest's audion that provided the crucial sound amplification.

In 1907, two years before America's first commercial radio station -- KQW in San Jose, California -- went on the air, de Forest was already broadcasting music from his New York office. In 1916 he gave the first-ever election-night coverage of a presidential race. In 1923 -- four years before The Jazz Singer -- he demonstrated a process for motion pictures with sound, for which he was later given a special Oscar.

De Forest received more than 300 patents in his career. The last one, for an automatic telephone dialing device, was granted when he was 84. Along the way he gained and lost three fortunes, married four times, rose to international fame and sank into obscurity. When he died in 1961, only $1,250 remained of the millions he had earned. His funeral attracted 35 people, and he was interred with simple rites performed by a Catholic priest.

EMPIRE OF THE AIR

De Forest's remarkable life story is breathtakingly told in Tom Lewis' 1991 book Empire of the Air: The Men Who Made Radio (HarperCollins), and in Ken Burns' two-hour documentary of the same name, shown nationally on public television. The title comes from de Forest's 1950 autobiography, Father of Radio, in which he wrote: "I had discovered an Invisible Empire of the Air, intangible, yet solid as granite, whose structure shall persist while man inhabits the planet..."

The two other main characters of the book are Howard Armstrong, who invented FM and adapted the de Forest's audion into a far more powerful transmitter and receiver, and David Sarnoff, the visionary executive who made RCA -- now known as NBC -- into the world's leading communications network.

December 1992 saw the publication of Lee de Forest and the Fatherhood of Radio by James A. Hijiya (Lehigh University Press, $32.50). Rather than simply analyzing de Forest's contribution to technology, it is a psychological study, tracing the inventor's spiritual quest. He emerges as a tragic figure, defeated in the end by the establishment he always fought against, and embittered by a world that had long since forgotten him.

HERMON DAYS

Born in Iowa in 1873, Lee grew up in Talladega, Alabama, the son of Congregational minister Henry De Forest, president of a struggling college for freed blacks. Discouraged from associating with the black children and shunned by whites as a hated Yankee, Lee lost himself in the school library, where he thrilled in stories about Edison, Bell, and other great inventors. Lee resolved to be one of them. Radio waves were discovered in 1887, and they came to obsess him.

Henry De Forest was an admirer of evangelist Dwight Moody, and knew of his two schools in northwestern Massachusetts. He enrolled his daughter Mary at Northfield in 1889, Lee at Mount Hermon in 1891, and their brother Charles in 1893. The tuition, room and board was $100 a year. To keep costs down, the school had a strenuous work regimen.

Within a month of his arrival, Lee knew Mount Hermon was not for him. The combination of work and study was a "foolish scheme," a "diabolical system" to make "intelligent minds go to waste," he wrote in his journal -- a habit he kept throughout his life. He often paid other boys to do his chores.

Initially in awe of the big, brawny farm boys, Lee soon formed an opinion that they were "hayseeds, farmers, ignorant, uncouth, rough fellows." His classmates made fun of his broad nose, calling him "monkey face." An unpopular student, Lee kept to himself and had few friends, but often went to see his sister at Northfield, attending chapel with her or visiting her in the dormitory.

"I begin to think that as I am different & more sensible than most of the boys here so I will find in the world. People don't think for themselves & are poor fools," he wrote in his senior year.

He excelled in the sciences -- particularly physics, taught by Professor Charles Dickerson, one of the finest instructors Lee would ever encounter. Dickerson gave the boy encouragement, inspiration, and the incentive to study, and Lee grew to love him as "an elder brother." Decades later, Dickerson would tell him, "It was a delight to me to have you in my class, for your mind ran so quickly and so far ahead of the lesson for the day."

One-third of the physics textbook concerned electricity and magnetism. De Forest received the highest mark in the class, and particularly enjoyed the lab work. Because of his outstanding record, he was asked to give the Scientific Oration at his graduation.

Up until his death, de Forest kept on the wall of his study the framed autographs of three men he considered his mentors: Thomas Edison, Professor Willard Gibbs of Yale, and Professor Charles Dickerson.

EARLY SUCCESS

From Mount Hermon, de Forest went on to the Sheffield Scientific School at Yale University, where he remained as unpopular as ever. Despite his high achievement, he was passed over twice for membership in Sigma Xi, the scientific honorary society. Still, he had absolute faith in his own ability. When his hard-pressed family urged him to cut short his graduate studies, he dramatically responded that his education was "all important for the further future, for life, for destiny, & for the world."

After receiving his Ph.D. from Yale in 1899, de Forest began working for a wireless telegraph company. Soon he developed what he called a "responder," a detector of wireless signals that was superior to what Marconi himself was using. Moving to New York, he was persuaded by a shrewd promoter, Abraham White, to set up his own company and sell stock.

In 1904, the American de Forest Wireless Telegraph Company erected a 300-foot tower at the St. Louis World's Fair and sent messages as far as Chicago, for which he won an Exposition Grand Prize and Gold Medal. That same year, the Navy contracted with him to build powerful stations in Puerto Rico, Florida and Panama. As chief engineer, de Forest personally supervised construction at the sites.

When the Russo-Japanese War erupted in 1905, a de Forest transmitter enabled a London Times correspondent to scoop his rivals. When the US Navy's "Great White Fleet" made a goodwill tour of the world in 1908, they brought along 26 de Forest radio telephone sets.

Lee de Forest lost his first company through the mismanagement of its director, but his second one was an even greater success. At its peak in 1910, it boasted 70 stations in communication with 400 ships sailing on the Atlantic Ocean and the Great Lakes -- far more than its competitors. Then the bubble burst again and the company's smooth-talking director was sent to the federal penitentiary for stock fraud. De Forest was acquitted, and launched a third company.

World War I brought an insatiable demand for radio equipment. De Forest's company was swamped with orders from Allied armies, and he made large profits. During the war he sold AT&T the exclusive rights to his patents for $250,000, and earned another $175,000 on dividends from the De Forest Radio Telephone Company. "So at last -- after 17 years of hard & unrelenting struggle.... I've at last reached a safe & secure resting place," he recorded triumphantly in his journal. He and his third wife, an opera singer, spared no expense in their life of luxury.

BROAD-CASTING

Marconi, eight months younger than de Forest, did not invent radio. He invented wireless telegraphy, which could send only dots and dashes through the air. Marconi looked upon wireless as a means of point-to-point communication like the telephone, and never envisioned sending signals to a wide audience.

De Forest did, however. Starting in 1906, when it became possible to transmit sound for the first time, he immediately thought of broadcasting culture into people's homes.

He might have been the first to apply the term "broadcast" -- originally an agricultural term -- to radio. While sending music over the airwaves in 1907, he described it as "sweet melody broad-cast over the city & sea." In 1909 he "broadcast" an appeal for woman suffrage -- possibly the world's first radio propaganda. In 1910 he took his apparatus to the Metropolitan Opera House and transmitted the voice of Enrico Caruso.

In 1920, the US government forbade him from making further broadcasts, saying that it interfered with naval and commercial radio telephone communication and that "there is no room in the ether for entertainment." De Forest remained bitter about this decision for the rest of his life.

Radio was rapidly becoming a full-fledged craze. Between 1922 and 1923, number of commercial stations nationwide exploded from 30 to 556. That same year, 500,000 radio sets were produced. By 1933, there were over 19 million radios in operation in the US.

PHONOFILM

Leaving radio behind, de Forest turned to an entirely new field -- talking pictures. He called the process "phonofilm." Needing capital, he cashed in his radio earnings -- close to $1 million -- and invested it all in his new venture. Between 1923 and 1927 he made many films of celebrities, including George Jessel, Eddie Cantor, and Charles Lindbergh after his famous flight. In 1924 he invited President Calvin Coolidge and the other two major presidential candidates to his studio and recorded their speeches on phonofilm.

By 1924, when he made his first color feature, more than 30 theaters had been equipped for phonofilm and 50 others were awaiting installation. Then things began to go sour. The major studios blocked him, and his partner, Theodore Case, decided to go his own way, withdrawing permission to use his equipment. By 1926, most of de Forest's capital was gone. Facing insolvency, he was forced to sell the company in 1928; it went bankrupt soon after. Other inventors then surpassed him with their own processes for sound films. After consuming a decade of his life and nearly all his wealth, de Forest's talking-picture dream faded out.

FINAL YEARS

Moving to Hollywood in 1930, he met a 24-year-old actress, Marie Mosquini, who became his fourth wife that same year. De Forest, 57, found true marital happiness for the first time. A rising starlet who had been Will Rogers' leading lady in dozens of films, Marie gave up her career to devote her life to de Forest. For the next 30 years, they shared a small white mission-style house on Hollywood Boulevard.

In 1936 de Forest declared bankruptcy. Never again would he enjoy the security and independence of a personal fortune. He began working for other companies as a consultant, doing most of the work in his own small lab and sending in his reports. Always energetic, he climbed Mount Whitney, the highest peak in the continental United States, several times, up to his 70th birthday.

His final years brought some honors, but too little, too late. From 1951-56, the American Television Company manufactured the de Forest 44, a premier line of 16-inch and 19-inch TVs. In 1957 he was the featured guest on Ralph Edwards' television show, This Is Your Life. In 1958, the town of his birth, Council Bluffs, Iowa, dedicated the Lee de Forest Elementary School. But a serious heart attack in 1957 and a prolonged illness exhausted his savings. When he died, his entire estate consisted of a few final paychecks from Bell Labs. He was buried in the San Fernando Mission Cemetery, northeast of Los Angeles.

LASTING FAME

De Forest's failure to achieve the fame of an Edison or a Bell was due mainly to the times in which he lived. Always an outsider, he was one of the last of the lone wolf inventors, working for himself rather than a corporation. By the early 20th century, even the greatest inventors were producing only parts of a machine. The audion, the essential invention of the electronic age, could do nothing on its own, but only as a component. No one becomes famous for something people don't know they are using.

In 1955, looking to posterity, de Forest donated many of his writings to the Library of Congress. After his death, his widow gave his remaining papers and artifacts to the Douglas Perham Foundation in California. This collection was the centerpiece of the Foothill Electronics Museum, which opened in 1973 on the campus of Foothill College in Los Altos, 30 miles southeast of San Francisco. Over the next two decades, thousands of schoolchildren and radio buffs filed through the museum to learn about the self-styled "Father of Radio."

In 1991, short of classroom space, the college broke its contract with the Perham Foundation and forced the museum to close. The foundation won the lawsuit that followed, and was awarded $775,000. Today, the bulk of the De Forest Memorial Archives rests in acid-free boxes in a vacant factory in Sunnyvale, in the heart of Silicon Valley -- an area that might not exist if not for the audion. The Perham Foundation has an archivist working on the documents several days a week, and makes them available to scholars.

NEW MUSEUM

The foundation's next step is to establish a new electronics museum in San Jose. The chosen site is in the 25-acre San Jose Historical Museum section of Kelley Park, which already has some two dozen buildings depicting San Jose at the turn of the century. To house the electronics museum, the foundation hopes to re-create the original bank building from which the first radio station in America was broadcast in 1909.

"They have wanted us to come down there for years," says Donald Koijane, a board member of the Perham Foundation. "They think we will be a cornerstone of their museum, because San Jose is trying to be known nationwide as the capital of Silicon Valley. We prefer to concentrate on the pre-silicon, pre-transistor days, starting around 1900."

The San Jose City Council is expected to vote on the proposal by early 1994. Approval seems likely, but even with a green light, it will take years for the new museum to be designed and completed. The foundation's large endowment will merely be the seed money for a building that will cost many times that amount.

The de Forest Memorial Archives, which make up about 20 percent of the foundation's collection, are sure to be one of the main focal points of the new museum. For Lee de Forest, it's just another chapter in his quest for immortality.

(Note: Lee de Forest's father spelled his name De Forest, with a capital D, while Lee spelled it with a small d.)